How Would You Measure The Speed Of An Animal

It's not quite Due east=mc2, but scientists unveiled Mon a simple, powerful formula that explains why some animals run, fly and swim faster than all others.

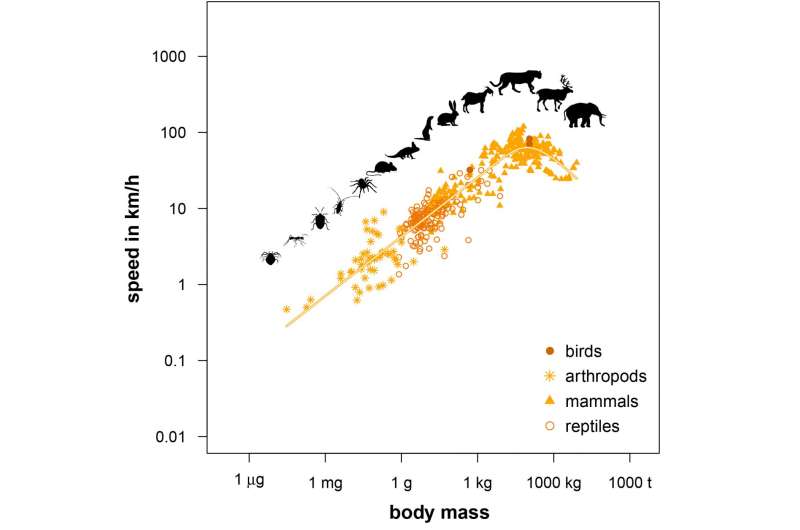

Call it the "speed rule": strength alone does non make up one's mind top velocity considering land mammals, birds and fish can only accelerate for every bit long as they tin draw from available energy stored in muscle tissue.

An intermediate body size—think cheetah, falcon or marlin—is optimal for striking that sweetness spot between brawn and energy burst, the researchers discovered.

Too pocket-size, and there's not enough musculature; also big, and there's too much mass.

Knowing simply an fauna's weight and the medium it moves in—water, air or across land—is plenty to summate its maximum speed with 90 pct accuracy, they found.

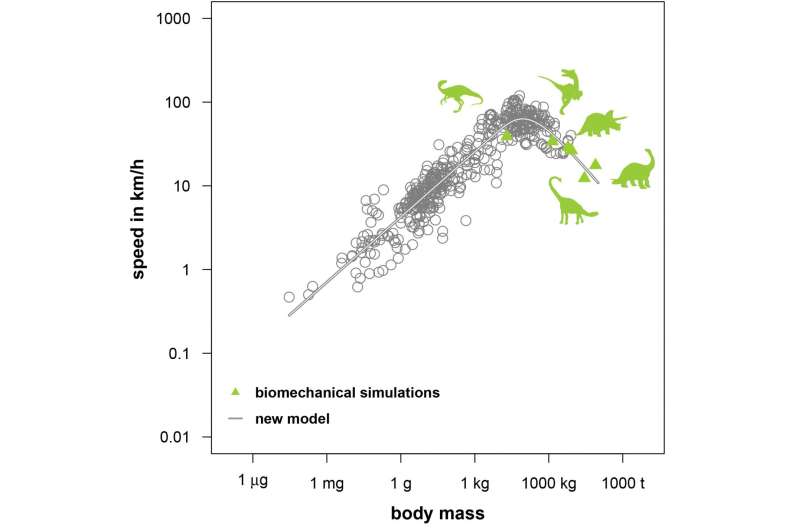

The axiom fifty-fifty works retroactively for dinosaurs, they reported in the periodical Nature Environmental & Development.

"Scientists have long struggled with the fact that the largest animals are not the fastest," said lead author Myriam Hirt, a biologist at the German Centre for Integrative Biodiversity Enquiry in Leipzig.

If muscles were all that mattered "elephants would reach maximum speeds of about 600 kph (370 mph)," she told AFP.

Instead, tuskers height at about 34 kph (21 mph).

Large beasts, in other words, run out of then-called anaerobic energy, supplied by the muscles, before being able to reach their theoretically maximum speed.

Amidst birds, falcons and hawks are the fleetest, clocking speeds well in excess of 140 kph (87 mph). Nearly as fast, the rock dove, wandering albatross and Rise frigate could fly in their slipstream.

Cheetahs hold the land record, comfortably topping 100 kph (62 mph).

Not coincidentally, one of the their preferred prey—the springbok—can run most equally fast, along with other antelope, such every bit the blackbuck, historically hunted by big cats.

T-rex not fleet of foot

That'southward evolution at piece of work, explained Hirt.

"Species that gain the most selective advantage—predators and prey with few places to hibernate, for example—will approach the predicted maximum speeds," she said.

Humans, by contrast, have non evolved over millions of years to outrun fast prey (or predators), even if they fall within the intermediate weight class corresponding to extreme speed.

Man sapiens, information technology seems, invested in outsmarting other animals instead.

Long-limbed giraffes tin can hit 60 kph (37 mph) when motivated, and bears—grizzly, dark-brown and polar—can top 45 kph (28 mph) for a few seconds before their fat-laden bodies slow them downwards.

The black marlin holds the known record in the sea, slicing through water at expressway speeds of 130 kph (fourscore mph), even faster than its quick cousin the Atlantic sailfish.

Total-grown Yellow fin and bluefin tuna can swim seventy kph (43 mph), simply slightly faster than the quickest shark, the shortfin mako.

Killer whales—which, like humans, teach their young hunting techniques—are somewhat slower, but reign unchallenged at the top of the marine food chain.

Birthday, the researchers tested their new hypothesis against data on 454 species weighing in at ane gram to 10 tonnes, from molluscs to blue whales, from gnats to whopper swans.

"Hirt and colleagues provide a unifying explanation for what sets the limits to maximum speed," Christopher Clemente and Peter Bishop, scientists at the University of the Sunshine Declension in Australia, wrote in a annotate.

"The exciting role ... is that it applies equally well to animals on land, in the air and in water."

And to dinos, too.

The model matched data on the handful of dinosaurs for which scientists have been able to estimate running speeds.

The study estimates that lithe velociraptors could sprint at 50 kph (31 mph), while the lumbering T-rex could barely movement at half that pace.

Only that was withal quick enough to grab a found-eating Triceratops or the fifty-fifty slower Brachiosaurus, meals fit for the dino rex.

The magic formula, past the style, is one thousand=cMd-1. (where k—acceleration constant, M—body mass)

More information: Myriam R. Hirt et al, A general scaling law reveals why the largest animals are not the fastest, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2017). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-017-0241-4

© 2017 AFP

Commendation: Size key to summit speed in animals, study finds (2017, July 17) retrieved 26 April 2022 from https://phys.org/news/2017-07-size-key-animals.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of individual study or research, no part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.

Source: https://phys.org/news/2017-07-size-key-animals.html

Posted by: bradleypand1956.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Would You Measure The Speed Of An Animal"

Post a Comment